“There is really, absolutely positively, no way we could have seen this coming”

Houston Post, 09/30/1936: "For years we have stood by idly while this tremendous waste of human life, property and resources went on unchecked and the State was impoverished."

Part 1: Boerne, Texas: A river runs through it.

Part 2: “There is no way we could have seen this coming”

Where we left off: They had finally put the flood of July 1932 behind them. Tourists once again came to Kerrville. Campers said teary goodbyes before heading back to Houston, San Antonio, Austin for school. Fishing industry was doing great. All was right with the world.

No one could have known. This could not have been predicted. There will never be a flood like this one. Heaviest rains in the history of Texas.

September 1932: Guadalupe River (Kerrville)

On September 15, 1932, a wiseacre with the Dallas News commented, and the Kerrville Mountain Sun reposted: “Ever since John Garner declared himself thoroughly wet, West Texas has been deluged with floods. If he wishes to win favor in that delightful part of Texas, he better follow Vice President Curtis’ example and declare himself dry. It is no joke to have numerous inches of rain dumped all at once on that area, flooding valleys, destroying property and taking human life. Mr. Garner ought to disavow responsibility and try to lay the blame on the Hoover administration.”

Even the battle over Prohibition figured into Texas’ flooding debate. Anything but actual solutions.

Less than two weeks later, the rain still had not stopped. Slowed, but not stopped. Seven days ended Wednesday September 28, 1932, an additional 4-7” of rain had fallen in Kerr County. That caused a rise of four to twelve feet, depending on location. On Friday September 23, a betrothed couple, Fred Tullos and Cleo MacCullum, dined at the River Inn Resort, next door to Camp Mystic, and like that camp, directly in the floodplain.

Apparently unaware that the Guadalupe was rising fast, they attempted to cross the river via a nearby low-water bridge. Their car was smashed to bits on the rocks. They and their dog perished.

October 6, businessmen in Kerr County expressed their anger over lack of action by County Commissioners. Everyone knew that there were not nearly enough bridges, low- or high-water. People were dying, for chrissakes. “Before the last rainy spell of weather, the Harper-Kerrville [road] was bad, but now it’s hell!”

October 27, 1932: Mrs. E.J. Stewart, owner of Camp Mystic, reported on construction progress. The cabins destroyed in July 1932 were being replaced, soooort of higher up. Still in the floodplain, although the reporter did not insult that woman by mentioning such an uncomfortable fact. Sleeping cabins were being built on the lower level, right up against the “bottom of the towering hills.”

They were reinforcing buildings already on high land, such as the dining hall. And they were building new housing for the director! All new buildings were to be rock-trimmed. On higher ground.

But those sleeping cabins? Still in the floodplain.

January 19, 1933: It became perfectly clear that FDR had won the election in November 1932. On January 19, Kerr County received $2000 [$50,000 in today’s currency] in Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) funds, part of FDR’s earliest New Deal. The funds were to go to unemployed persons. Remember, the 1932 flood occurred while the Great Depression with its inconceivable levels of unemployment was in full swing. Able-bodied men were to be paid $1.50 per day [$37] to clear debris along the Guadalupe. It wasn’t much money, but it was better than nothing.

A week later, Kerrville Times reported thirty-two men had received RFC funds. The Mountain Sun said it was 75. Never mind. People were finally earning a bit of money to feed their families, and visible reminders of July 1932 were finally being eradicated. The RFC program had been so successful, County Commissioners announced their intention to file for more grant money from the federal government.

April 20, 1933: The good people of Kerr County may not have liked FDR all that much, and that New Deal of his was certainly thinly-disguised Communism. But boy howdy, did they ever love the money he was sending their way! President Roosevelt allotted 11,750 men to Texas under the federal government’s $500 million [$2.3 billion] reforestation plan.

Since Texas had little need for reforestation, state officials had been able to convince the federal government to use most of its allotment for soil erosion, flood control, and parks. Kerr County expected to receive grant money for a camp of 200 men who would especially focus on the Guadalupe River. County Commissioners along the Colorado, Brazos, Nueces, Rio Grande, Trinity, Red, Sabine, Sulphur, and Neches Rivers, as well as along Angelina and Toyah Creeks, expected to have similar funding and manpower.

Full employment for 200 men! The Mountain Sun urged the desperately unemployed to wait for hiring notices and not to contact County Commissioners just yet.

September 1936: Guadalupe, Concho, Llano, Leon, and Nueces Rivers, and Pecan Bayou (Kerrville, Uvalde, Llano, Fredericksburg, Gonzales)

Summers of 1933, 1934, and 1935, newspapers across Texas patted themselves on the back. No floods! Hill Country camps full to overflowing. Tourism on the rise! Heroes of 1932 were recognized for their bravery as the anniversary of the July 1932 flood came and went three times.

And then it rained. Twelve inches along the Nueces River. Twelve inches in San Angelo. It only rained 4.94” in Kerrville, but the Guadalupe rose to a 22’ stage. It only rained 4” along the Llano, but the river was reported at a 22’ stage. The Guadalupe crested at 24’ in Gonzales. Seven inches of rain near the Colorado River threatened to destroy the Roy Inks Dam near Burnet.

Bridges were out. Goats were washed downstream. Trains were cancelled. Creeks near Sonora washed away houses. Telephone lines were downed.

One more time, the editor of the Houston Post asked for reform at the state level. Fifteen years after the editor begged for statesmanship, yet another editor begged for public officials to do something.

The Colorado, the Brazos, the San Jacinto, the Trinity, the Guadalupe and many lesser streams annually exact heavy toll of human life and property. They pour their muddy waters over some of the most fertile farming land in the Southwest, driving human beings from their homes, ruining crops, washing out highways and railroads and leaving hundreds homeless and destitute.

The damage by erosion of the soil, a direct result of the floods, is enormous. Every year millions of dollars of fertile soil is washed into the Gulf of Mexico and Texas is permanently deprived of an irreplaceable resource. …

Here is a problem that challenges the best efforts of every public official in Texas and every patriotic private citizen. For years we have stood by idly while this tremendous waste of human life, property and resources went on unchecked and the State was impoverished. …

This city [Houston] not only should work for adequate flood control structure to protect the community, but for a co-ordinated flood control plan for all Texas.

One more time, good words fell on deaf ears.

And… it would not stop raining. 4” today, 2” tomorrow, 5” the next day. Now the Brazos, tomorrow the Colorado. Belton under water. Levees at Waco destroyed. Pecan Bayou — a tributary of the Colorado, but a bayou! — crested at 36’. It became too overwhelming for reporters to keep track of, the damage too extensive, the resulting homelessness, hunger, distress too immense.

Kerrville, Comfort, Legion, Hunt, Center Point, once more under water. Once more isolated. In Center Point, the Guadalupe reached a height of 30’, in Comfort, 35’. And there had not been that much rain. What was going on?

The flood of 1936, rarely mentioned in historical accounts because there were so few lives lost, was so significant that Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Department of the Interior under FDR, commissioned a special report. Tate Dalrymple and others wrote that the rains from September 14 through September 30, 1936, combined with earlier summer rains in late June and early July, “produced floods on the lower Guadalupe River and several tributaries that were greater than had ever been known.”

Dalrymple recognized that they had been collecting insufficient data, merely looking at river height, flow, and other basic information. They must expand scope and detail to include source of rainfall that caused these floods. FDR’s Public Works Administration allotted $10,000 [$231,000] to the US Geological Survey department “for investigation of stages and discharges of floods…” Science was finally being used to analyze what was going on, thanks to New Deal funding.

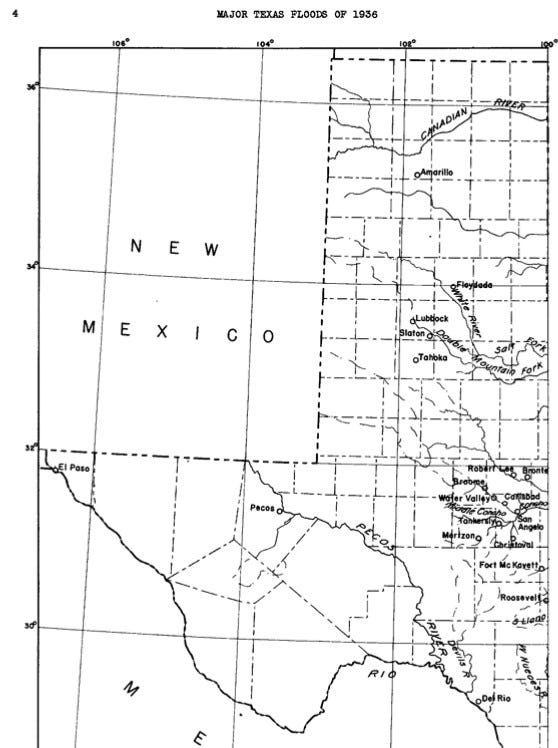

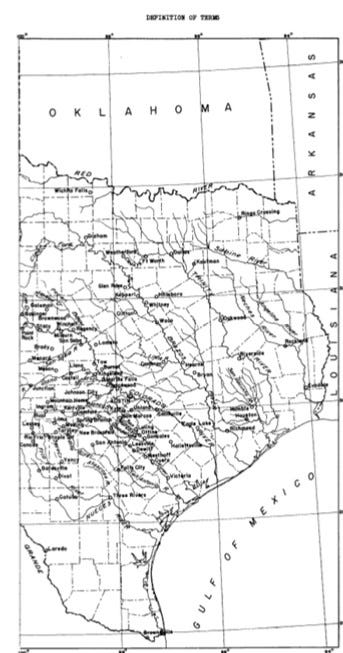

His discoveries based on extraordinarily detailed data revealed that flooding from June through September 1936 — solely related to rising rivers, nothing along the Gulf Coast — affected 2,000,000 square miles, or one-fourth of Texas. Dalrymple’s team analyzed information collected along 884 miles of rivers, creeks, and streams. They further mapped the interconnected waterways. The maps alone are worth the price of admission.

Meanwhile, people on the ground could only wonder how so little rain could cause such massive flooding. And damage. At least this time, with no loss of life.

February 18, 1937: Texas legislators, realizing that Harold Ickes controlled the purse strings for flood control projects, played nice and made him their guest of honor. Lower Colorado River Authority invited Ickes to Texas. The state legislature asked him to speak at a joint session in Austin. Ickes would also tour Buchanan Dam, Roy Inks Dam, and the planned construction site for Marshall Ford Dam.

Construction on Buchanan Dam had begun in 1931 and was originally named the George W. Hamilton Dam. The Great Depression caused the state-funded public utility commission to go under and construction ceased. In 1934, US Rep. James Buchanan obtained funding from FDR’s Public Works Commission to finish the dam, and upon completion in 1937, it was named for him.

Roy Inks Dam was another FDR/Public Works Commission project, started in 1936 and completed in 1938. Marshall Ford Dam (now Mansfield Dam) was also an FDR/Public Works Administration flood control project.

But Texas don’t need no stinkin’ federal guvmint, do they?

September 1952: Guadalupe, Pedernales, Blanco, San Marcos, and Comal Rivers and Cibolo, Town, Cherokee, and Barons Creeks (Kerrville, Fredericksburg, Comfort, San Saba, Johnson City, Marble Falls, Boerne, New Braunfels, Beeville, Luling)

Central Texas had endured a long and painful drought, when it suddenly started to rain on Wednesday, September 10, 1952. “Almost every town in the Hill Country of South Central Texas had 10 to 20 inches of rain,” the Houston Post reporter said. He added that dams along those rivers would prevent flooding downstream in the Houston area.

The Houston YMCA Camp in San Marcos was under fifteen feet of water. No deaths, because it was empty. Same old story. Roads closed. Bridges out. Telephone lines down.

Unidentified body found in Blanco. F.A. McKinney drowned in Fredericksburg. Edgar Kneupper and Aurentino Castillo missing near New Braunfels. An unidentified person dead in Boerne. The recently widowed Mrs. Wilkins of Gladewater drowned in her car. A four-year-old girl named Ernestina Rodriguez (from Houston) drowned in Pedernales flood waters. The governor dispatched the National Guard to New Braunfels for search and rescue.

Guadalupe River in Seguin, near New Braunfels, was running 33’. Lower Colorado River Authority said the Pedernales “was on its biggest flood on record.” The Blanco River reached 50’ at Johnson City. Previous record had been 33’ in 1869. Fifty families in Marble Falls were being evacuated, but those newly-built dams protected the townships of Granite Shoals and the rest of Marble Falls. In Gonzales, at the confluence of the Guadalupe and San Marcos Rivers, the river crest reached 34.3’ — but over 3000 people went to the Friday night high school football game anyway.

In addition to those life-saving dams, technology enabled the National Guard to rescue Texans who would have died had this flood taken place in earlier years. Helicopters lifted people off rooftops, cars, trees. Amphibious DUKWs or “ducks,” invented for use in World War II, plunged into raging rivers, saving people barely staying afloat.

When all the damage was tallied, the official records showed that eight had died, flood damage was roughly $10.8 million [$131 million], with hundreds, if not thousands, of Texans homeless.

One very, very positive result of the September 1952 flood: Since federal money was still available, people along the Guadalupe finally got serious about flood control — at least the part that would not cost them any money. Canyon Dam, forming Canyon Lake, was approved in 1954. Construction started in 1958, completed in 1964.

September 1964: Rio Grande, and Cibolo Creek (Laredo, San Antonio, Boerne)

The flood that took out Uncle Martin’s business impacted a relatively small part of Texas. San Antonio and nearby Boerne suffered the most damage, with only one death — in Boerne. San Antonio itself received only 1” of rain, while Boerne was hit with 6” of rain in a sudden downpour, too much for the dry creekbed of Cibolo Creek to absorb.

The Houston Post noted that 5” of rain near Medina Lake caused a 25’ rise.

Laredo had been hit by back to back flooding from the Rio Grande. The first flood (Friday, September 25, 1964) left 5000 people homeless. The second crest, expected on Monday afternoon, September 28, would likely be two feet higher than previous records. That flooding barely registered outside South Texas.

May 1972: Guadalupe, Comal, and Navidad Rivers and Blueders Creek (New Braunfels, San Antonio, Edna, Gonzales)

May 7, I noted in my diary, “Rather uneventful day, except that it rained all day.” Every day for the rest of that week, my diary entries were headed with “still raining.” On May 13, the mood changed. “Twenty-four people were drowned because of flooding in New Braunfels! 10 inches fell there in an hour & a half yesterday… Comparatively, Houston got off light.” (Ellipses in original.)

Newspaper reports followed my eleventh-grade diary. May 9, three people drowned in a flash flood in San Antonio and another was still missing. Heavy rain, but nothing all that serious.

On May 13, the dispassionate tone disappeared. In New Braunfels, a cloudburst had released 10” of rain in less than an hour and a half. Houston Post said death toll stood at eleven and climbing. Around 3500 people had been forced to evacuate, while another 2000 voluntarily left town. San Antonio was flooded too, with 200 forced evacuations.

The New Braunfels dead included two notable citizens: Jeannie Faust, wife of a former mayor of the town. And Clarence Knetsch, formerly head of the Secret Service detail that guarded President Lyndon Johnson. The Faust’s home was one of those built very near to the river itself, a beautiful view when it wasn’t flooding. The former mayor survived by riding the river seven miles downstream. Mrs. Faust’s body was discovered fifteen miles downstream in Seguin.

As in 1952, the death toll would have been considerably higher without those dams, without helicopters. High-water marks showed the river had surged 35’ over its banks. The New Braunfels City Manager bemoaned the lack of a warning system. “We didn’t have much time to give the people much warning,” he told an Associated Press reporter. “It all happened so fast.”

The Teague family from Houston had been staying at a riverfront home. As waters rose, they climbed on top of the roof. Flood waters eventually swept them off the roof. Some survived by hanging onto the branches of a nearby tree. Two held onto telephone wires. Four-year-old Sara could not manage either of those safety nets and drowned in the flood waters.

And. It. Kept. Raining.

Around midnight, new flash flood warnings were issued. A fifth of New Braunfels had already been destroyed. What more could the Comal do to them?

By Monday, the death toll had risen to fifteen, with many more missing. Incalculable damage. Fancy houses of Houston’s elite, as well as humble clapboard homes, all placed on that envied Comal riverfront in 100-year flood plains, wiped away.

Also by Monday, people in Houston started worrying. Flood control for the Guadalupe was still minimal. Basically Canyon Dam… What would happen in Victoria? When the wall of water roared through Cuero, where Martindale cousins had moved, that wall had been 35.2’. That same amount of water in Victoria would be devastating.

Although “a ridiculously small number of homeowners in flood-ravaged Seguin, San Marcos and New Braunfels were covered by flood insurance” (Houston Post), Gov. Preston Smith, Democrat, and Senator John Tower, Republican, were absolutely certain that President Richard Nixon would declare Hays, Comal, and Guadalupe Counties a disaster area and send federal funds to bail them out.

And it kept on raining. For several days after the worst of the flooding, flash flood watches remained in effect from New Braunfels to Victoria. Final death toll: Sixteen. They stopped counting the homeless.

July 1987: Guadalupe River and Cypress Creek (Kerrville, Hunt, Comfort)

The Houston Post ran a fun summertime article on July 17, 1987. “A-tubing we will go,” proclaimed AP reporter Laura Lippman. Lippman provided safety tips for the novice tuber, including the wearing of sunscreen. She also advised that anyone planning a trip to New Braunfels or the Kerrville area first check river flow reports. Lippman gave good counsel regarding when the Guadalupe or Comal Rivers were too low, too high, too fast, too slow. She also noted that since rainfall had been especially high in the summer of 1987, that meant higher than normal release rates from Canyon Dam. That had made the flow rate “exceptionally dangerous,” she wrote. Better to go rafting. With a guide.

River forecasts posted the same day in the Post seemed innocuous. “Rivers expected to remain within banks,” they said. Including the Guadalupe.

That forecast was proved dreadfully inaccurate. It rained, maybe 11”, through the night. Initial wall of water was 16’ high. Post reporter Pete Wittenberg said the beautiful Guadalupe “turned into a writhing, wrathful witch.” In Hunt, site of all those summer camps, “the river peaked at 28.4’ at 5 a.m.,” he wrote. It continued to rise, cresting at 30’ around noon. Still bad, but not like 1978, and certainly not like 1932.

Canyon Lake should protect cities and towns downstream, but meteorologists watched the forecasts with more than a little fear. Canyon Lake could handle the rainfall and flooding that swept through Kerrville and Hunt, but additional rain would strain the dam.

The news would quickly worsen. On Saturday July 18, the Post said that a bus and van carrying campers across the Guadalupe had been swept away by flood waters, killing at least two, critically injuring two more, with thirty-one more treated at area hospitals and released. And some kids were missing.

Locals could not understand how or why the bus and van ended up submerged. Nolan Lewis, special to the Post, interviewed people from Kerr County. They said that around 6 o’clock in the morning, Kerr County sheriff’s deputies drove along Water Street, sirens blazing, yelling to people to evacuate to higher ground. Without the dedication of those deputies, the death toll could have been astronomical. Because Camp Mystic had rebuilt along the river’s edge, and its campers would have been sleeping.

So why did a church bus and a church van try to cross a low-water bridge across Cypress Creek? Why?

Lewis continued talking to people. He noticed that non-Texans placed their gear down next to fire ant mounds. Rookie mistake. Everyone waited to see what would happen when the big bus painted with Seagoville Road Baptist Church was lifted from the muddy water.

Rainfall totals leading up to this disaster had been all over the board. Boerne, 0.08”. Ingram, 4”. Kerrville, 3.33”. New Braunfels, 0.55”. None of those numbers anticipated flood waters of this magnitude. Wait, Hunt: 11”! No wonder the Guadalupe “crested 16 feet over flood level, 5 feet higher than previous record in 1932 flood,” so the Post. Eleven inches of rain.

Mark Sanders reported that men participating in regularly-scheduled Army Reserve training exercises at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio were drafted into search and rescue efforts. Technology in 1987 was improved even over that employed in 1952 and 1972. Not only helicopters, but divers in wet suits, “flying ambulances,” military-grade rafts, all were put into service, looking for survivors.

Because of the early — and persistent and loud — warnings, none of the camps except Pot O’ Gold reported loss of life. Counsellors rousted campers from their beds, got them to high ground, and fed them breakfast. On July 18, some interviewed wondered at the people from Camp Pot O’ Gold sending kids in vehicles across a low-water bridge, instead of leading them to higher ground. The camp next door to Pot O’ Gold had evacuated its teenage girls to a nursing home higher up the hill. The girls reportedly had a blast.

Both the Houston Post and the Kerrville Times did something more than a little controversial on July 18. Melanie Finley, one of the two teenagers from Pot O’ Gold who died, did not drown. A helicopter tried to rescue her. Initially she fell back into the river. On her second attempt, she fell onto land and died. Both newspapers published a photo of her falling from the helicopter, in mid-air.

Sunday, July 19, another casualty was added to the list of dead. A man who had ignored warnings regarding tubing on the Guadalupe.

By Tuesday July 21, they were closing in on final tallies. Nine dead, one still missing (that child would later be found drowned as well, wrapped in a barbed wire fence). The National Transportation Safety Board issued its preliminary report regarding the Seagoville Baptist buses. Fault did not lie with the bus or van drivers, they said. Those drivers had followed the evacuation plan provided by the camp owners.

There was a heated debate over timely warning. Fire department insisted that Pot O’ Gold had received the same 5:30 and 6:00 a.m. warnings as everyone else. Pot O’ Gold camp director insisted they had not.

Nevertheless, when five buses and a van left at 7:30 a.m., they followed the camp’s primary evacuation route. That route entailed turning left onto Hermann Sons road, avoiding the low-water bridge that they’d have encountered had they turned right. Turning left would take them to high ground. But turning left also took the buses and van into water that was swift and rising fast.

The first three buses made it through the waters of the Guadalupe safely. The fourth bus stalled in the rapidly rising river. The van following it could not back up. The fifth bus did indeed back out of the floodwater, otherwise the number of deaths would have been greater. Both the bus and van drivers ordered their teenaged passengers out into the river, where they were swept downstream.

Baffling to everyone writing about the story: Why did those buses and van leave at all? Pot O’ Gold was one of the few camps on high ground. If they had stayed put, there would have been no deaths.

In the end, ten teenagers died, plus one older “tuber,” and thirty-three teens were injured.

No one could have known. This could not have been predicted. There will never be a flood like this one. Heaviest rains in the history of Texas.

References.

Bonavita, Fred and Michael Haederle. “Guadalupe death toll grows to 8.” Houston Post. July 19, 1987, p. 1.

Dalrymple, Tate and others (1937). Major Texas Floods of 1936. United States Department of the Interior in cooperation with Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works.

Haederle, Michael. “Survivors recall bravery of peers.” Houston Post. July 19, 1987, p. 3.

-----. “Drivers followed correct route.” Houston Post. July 21, 1987, p. 17.

Kerr, Katherine. “3rd body recovered from river: 7 campers still missing.” Houston Post. July 19, 1987, p. 1.

Kimball, Allan and Mary Flood. “Camp Check: Flooding posed no problems for many along river.” Houston Post. July 18, 1987, p. 12.

Laws, Jerry. “Waiting for Word: Members join in somber vigil at academy.” Houston Post. July 18, 1987, p. 12.

Lewis, Nolan. “Rescuers pull together to drag bus from river.” Houston Post. July 18, 1987, p. 13.

-----. “At river’s edge, kids with bikes, girls with tears.” Houston Post. July 19, 1987, p. 3.

Lippman, Laura. “A-tubing we will go.” Houston Post. July 17, 1987, p. 64.

Sanders, Mark. “The Rescuers: Routine duty turns into grim search for bodies.” Houston Post. July 18, 1987, p. 12.

Wittenberg, Pete. “Guadalupe pounds through resort areas.” Houston Post, July 18, 1987, p. 13.

-----. “Saintly Guadalupe turns to wrathful witch.” Houston Post. July 18, 1987, p. 3.

Abilene Reporter-News: September 28, 1964, p. 14.

Austin American: September 28, 1964, p. 14.

Austin American-Statesman: September 28, 1964, p. 1.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram: September 30, 1964, p. 18.

Fredericksburg Standard: September 30, 1964, p. 12.

Houston Post: September 16, 1936, p. 1; September 17, 1936, pp. 1, 6; September 22, 1936, p. 6; September 29, 1936, p. 2; September 30, 1936, p. 3; September 11, 1952, p. 1; September 12, 1952, pp. 1, 4; September 13, 1952, p. 1; September 14, 1952, p. 13; September 15, 1952, p. 1; September 28, 1964, p. 14; May 9, 1972, p. 12; May 13, 1972, pp. 1, 12; May 14, 1972, pp. 1, 2; May 16, 1972, p. 6; May 17, 1972, p. 25; May 18, 1972, p. 26; July 17, 1987, p. 4; July 18, 1987, pp. 3, 5, 13, 22; July 20, 1987, p. 14.

Kerrville Mountain Sun: September 15, 1932, p. 4; September 29, 1932, pp. 1, 10; October 6, 1932, p. 4; October 27, 1932, p. 5; January 19, 1933; January 26, 1933, p. 1; April 20, 1933, p. 1; June 8, 1933, p. 4; May 3, 1934, p. 1; October 1, 1936, p. 1; February 18, 1937, p. 10.

Kerrville Times: January 26, 1933, p. 1.

McKinney Courier-Gazette: September 28, 1964, p. 1.

Mexia Daily News: September 29, 1964, p. 1.

San Antonio Express-News: September 28, 1964, p. 1; September 29, 1964, pp. 10, 18.

Waco News-Tribune: September 28, 1964, p. 1.

© 2025 Denise Elaine Heap. Please message me for permission to quote.

Now More Than Ever is a reader-supported publication. To receive email notifications regarding new posts, and to amplify my voice here on Substack, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

If you’d simply like to leave a tip for this specific post, I would be grateful!

Before my grandparents moved to San Marcos and Martindale, they and their people lived along the Frio River in Leakey and Sabinal. I remember when we built our house on our Hays County ranch, my grandfather came and helped choose the site so it wouldn't flood. Old-timers like him knew how to guess water flow based on the shape of the canyons and their water marks. People looked at the contours of the land and they knew what it meant. You also got an important clue from how high old debris from previous floods was lodged up in the trees.

To this day, I really don't like not having my house on high ground. You can always go down to the river or creek to fish, but come back up to sleep.

Thank you so much for this excellent summary. Can’t wait to read part 3! And I guess part 1 if this was part 2?

I worked at 2 different camps year round in the mid-90s in the Hunt area. They were still talking about the ‘87 flood and the campers that were swept away back then. At one of the camps (it was on a 40,000 acre ranch) we would hike the kids a couple of miles out from camp base to backcountry campsites, teaching them about edible plants, tracking tips, geology, etc. along the way. We always hiked some in a draw and would ask kids how high they thought the water could get when big rains came. They were always amazed to realize that the debris stuck in trees so far above their heads was the high water mark.

We used to get gullywashers fairly regularly, and we knew exactly what roads would flood out. All of our housing was not necessarily near camp; it could be miles away in a different part of the ranch. One time the rain came and we purposefully situated ourselves at one of the houses we knew would be cut off so we would be guaranteed a day or two off because we wouldn’t be able to drive to camp the next day (we didn’t have campers at the time). Our plan worked, but then we got bored and by mid morning ended up hiking through the woods to camp anyway, (avoiding flooded areas of course) to be with everyone else. 😂