“There is no way we could have seen this coming”

Houston Post, 9/14/1921: "Will the indifference of the past 76 years continue indefinitely, in spite of the painful lessons that are forced upon us year after year?"

Part 1: Boerne, Texas: A river runs through it.

This was intended as a two-parter. But the details are so eerily similar to details we’re reading about the 2025 flood, I couldn’t shortchange the people who survived to write about the floods of 1921. Of 1930 (two floods). And of July 1932. And of October 1932. And 1952 and 1964 and 1972 and 1987. Just telling those stories skips hundreds others equally heartrending.

Someone should start this conversation out loud. Should hold the feet of Texas officials to the fire. Wait till you read excerpts from the Houston Post editorial following the 1921 flood. Déjà vu all over again. Get a cuppa, and enjoy.

On July 18, 1987, a staff writer for the Houston Post wrote, “If there’s one thing people living in the Hill Country around Kerrville have learned in coping with Texas weather, it’s that floods can be sudden and deadly. At least 715 people lost their lives in 32 separate floods throughout the state between 1899 and 1982.”

That anonymous journalist then lists fourteen of the “32 separate floods,” with loss of life and property.

Two points of clarification.

First, there had been far more than thirty-two deadly floods in Texas at the time that journalist wrote that otherwise good article. Second, these are only floods on or near rivers. That journalist’s list omits floods from hurricanes, tropical storms, or other weather events.

Do I personally have an exact count? No. But if a person lives in Houston for any stretch of time, you know that West University Place-Rice University floods many times a year. In fact, an afternoon thunderstorm that drops 2” of rain anywhere close to Rice shuts down access to that part of the city. I also remember numerous floods near the Washington Avenue exit on I-10 in Houston, I believe several with at least one drowning.

And in 1900, the hurricane that devastated Galveston, Texas left between 6,000-12,000 known dead or missing. Flooding from Hurricane Harvey in 2017 left almost 100 dead. In fact, hurricane-related floods, together with loss of life and property, often overlap flash flooding near or on rivers.

Texas produces a goodly number of homegrown engineers, geologists, and meteorologists. Texas A&M, Rice, University of Texas — these have long traditions of engineering expertise. Aggieland prides itself as well on its research into freeway and road safety.

I would wager that if you fed these engineers, geologists, and meteorologists the data from Texas flooding from 1899 through present and let them develop regulations and laws to prevent deaths and loss of property, and if you further gave them, and not corrupt politicians, the right to enforce those regulations and laws, “flooding history” in Texas would have a much different face.

Following narrative therefore expresses highlights from that “flooding history,” limited solely to flash flooding on or near rivers, excluding events related solely to hurricanes and tropical storms. That said, I would want my dream team of engineers, geologists, and meteorologists to examine data from non-river floods as well.

September 1921: Rio Grande, San Antonio, Colorado, Guadalupe, San Pedro, Brazos, Little, and Pedernales Rivers, and Alazan Creek (Austin, San Antonio, and Central Texas)

It started easy. “Three-Inch Rainfall Breaks Lockhart Drouth,” said the small article in the Houston Post. Not enough to worry about. There had been some flooding along the Rio Grande. But few people were affected by rain down there.

Then it got real. The Houston Post reported that over 18.25” of rain fell in Austin on Saturday, September 10, 1921. Although the town also experienced damage from a tornado (Austin is part of Tornado Alley), rain caused most of the deaths and damage.

Austin and San Antonio may have born the brunt of flash flooding, but nearby towns such as Georgetown, Elroy, Creedmoor, and Pflugerville suffered too. While the San Antonio, Colorado, and San Pedro Rivers, along with Alazan Creek roared through towns and cities, smaller streams likewise overflowed. It’s all interconnected, streams, creeks, rivers.

It had rained all day that Saturday, September 10, 1921. 1921 had been a dry year. People living in Central Texas needed rain. Two full months had passed without a single drop of water. They were therefore glad to see storm clouds bringing rain.

But then it simply would not stop raining. From 7 o’clock on Saturday morning, it rained. Not the nice drizzles, the long rains that feed crops. No. Texas rain. Gully washer. All day. It kept raining.

Residents of San Antonio and Austin were worried, to be sure. Surely it could not keep raining. They went to bed, confident that it would stop raining as they slept.

But it did not stop raining. “Lightning flashed almost continuously and the thunder boomed and reverberated through the heavens,” the Post reporter wrote on Sunday. Sometime during the night, those who could not sleep heard an awful roar, “subdued but ominous.” And just like that, rivers reclaimed the shores of towns and cities along their respective banks.

Without immediate access to weather service data, townsfolk could only guess how high the wall of water had been. Ten feet, said some. Thirty feet, said others. Official reports would later record that the Colorado River rose 18’ in Austin. In a morbid footnote to the death and destruction, the Austin American said that as the river continued to rise — marking 20’ at midnight in Austin, and 35’ at the mouth of the Pedernales River — “scores of persons lined the Congress Avenue bridge until early this Sunday morning and watched the water, which lapped the green terrace of Riverside Park.”

Austin’s actual rainfall total of 19” was hardly the most for that September 1921 flood. Thrall, Texas saw 40” and a weather-tracking station in Williamson County reported 36”.

My paternal grandfather was a high school student in Taylor in 1921. His hometown saw 23.63” inches of rain within a twenty-four hour span. For several days, newspapers reported that as the most rainfall ever in Texas, apparently unaware of the records set in Thrall and elsewhere in Williamson County.

In nearby Smithville, the floodplain extended two miles beyond the Colorado. The Colorado had risen sixteen feet in ninety minutes. In Gonzales, the Guadalupe River crested at 31’. San Marcos, Blanco, New Braunfels, all were impacted, with reports of San Marcos completely under water.

Cameron, Texas got a foot of rain, and the Little River rose fifty feet. “Cameron is isolated from the world by flood waters,” said the Post reporter. Martindale, Fentress, Luling, my mother’s stomping grounds when she was young, all under water. Buildings that were 45’ above river banks, all under water. Even the skating rink at Fentress.

Houses were swept away by flood waters. Telephone wires went down. Power went out for the homes that had it, and for businesses. Oil pumps, gin mills, everything came to a standstill. Trains couldn’t get through as tracks and bridges had been washed away. Houston Post reporters assumed that whatever death count would eventually stand, it would be an undercount, due to bodies pushed downriver.

An Austin American reporter said that the desperation and flight of residents in the “thickly populated Mexican district” along Alazan Creek resembled refugees fleeing battle in World War I... without the advance warning of artillery fire. In news wrap-ups after the fact, reporters stated that almost 100 homes along Alazan Creek were completely demolished, leaving survivors homeless.

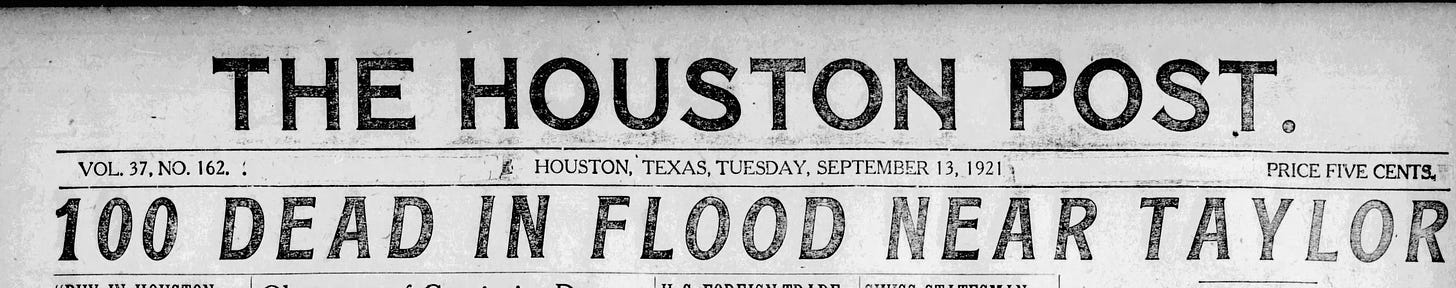

It was a “night of terror,” one that “exceeds all known stages,” said a reporter with the Houston Post on September 12. There were comparisons, to the flood in 1913, to the flood in 1845. No one could have known. This could not have been predicted. There will never be a flood like this one. Heaviest rains in the history of Texas.

Meanwhile, the death count kept rising. Forty here, sixty there, five in that house, two in the other one. One hundred, one hundred fifty, two hundred. Final count as reported in 1921: 250 dead. Later historians would say, 215. No matter.

Most of the dead were “Mexicans” who worked the farms of Central Texas. Also disproportionately affected, freed Blacks who lived in Texas “bottomlands.” One newspaper reported that these Blacks were conscripted to assist with search and rescue, as well as cleanup.

Still heralding the rainfall in Taylor as the most ever in Texas, the Houston Post surmised that these floods must have been caused by rain in north Texas. It had not rained that much in Central Texas. Not enough to cause this sort of flash flooding. [Historical footnote: It was caused by a Cat-1 tropical storm and affected over 10,000 square miles of Texas.]

On September 14, 1921, the Houston Post published an editorial that rings true 104 years later.

The flooded river valleys of Texas, with their heavy loss of life and property, tell no new story. These disasters have occurred at intervals as far back as our written records go. Of course, they are more disastrous now than in former years when the cities and towns of Texas were small, and when little land was tilled. [Then summarizes loss of life and property in previous years.]

Is not loss of this character preventable? If it is, why does not the State undertake to prevent it? … Where is our constructive statesmanship? Where is our constructive business ability? Our enterprise? …

Why is it not worth while for our best minds to evolve a feasible plan to save the people from the recurring losses, injury and bankruptcy that result from the twin evils of flood and drouth?

Why do we chase political will-o’-the-wisps, prejudices, fads, isms and buncombe every biennium, instead of striving for these great things that bear directly upon the wellbeing of the State and its people? …

Will the indifference of the past 76 years continue indefinitely, in spite of the painful lessons that are forced upon us year after year?

Sadly, Mr. Gold Viron Gribble Sanders (editor): It has continued for at least another 100 years.

May 1930: Guadalupe River (Kerrville, Boerne)

A mere 3-1/2” of rain over a week’s time caused major flooding in Kerrville and Boerne. Guadalupe River rose three feet. Accompanied by a lightning storm that took out the Kerrville Bakery and the home of Mrs. Bertha Schnerr.

Locals in Kerrville were concerned — less about flooding, and more about revenue. A businessman suggested they fund dams along the Guadalupe. Not for flood control, heavens to Betsy, no! For fishing. He was unable to stock a rapidly flowing river, so needed dams to increase his fishing business.

October 1930: Guadalupe River (Kerrville)

Kerrville received 7-1/4” of rain in a 24-hour period, the most since 1919. Nearby localities reported 10” in the same period. The rain “sent the river on an 18-foot rise, the highest stage reached in 11 years. The wall of water came down about 2 a.m. Monday [October 6, 1930], blocking all traffic on Highway 27 for more than 24 hours” (Kerrville Mountain Sun). The reporter further noted that the highest flood mark ever reached by the Guadalupe in Kerrville was 37’. In 1900.

Most damage occurred in nearby Legion, where four riverside cottages were swept away by the current. There were no deaths.

A couple of weeks later, the Kerrville Mountain Sun reported that the new dams along the Colorado River near Austin were to be telephoned-controlled. Cutting edge technology enabling humans to control raising or lowering of floodgates from a distance. The new technology would be tested at Kingsland Dam near Llano.

March 1931: The Kerrville Mountain Sun published a notice that the US Weather Bureau had 500 stations observing river stages on a daily basis. This enabled better forecasting, and timelier issuance of flood warnings.

November 1931: Kerr County officials recognized the need for “high-water bridges” for the safety of county residents. They commissioned the building of the first such bridge along Highway 81, then under construction.

June 1932: Kerrville Mountain Sun reported on advancements being made by US Weather Bureau. University of California’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography was researching the correlation between temperature and chemical content of sea water, and “weather.” The research had been underway for sixteen years and had improved quality of weather forecasting by a material margin. And their work was still in its infancy.

July 1932: Guadalupe River, as well as Nueces, Sabine, Frio, Blanco, and Leona Rivers (Kerrville and surrounding areas, Comfort, Uvalde, Ingram)

July 1, 1932, the rain started. So insignificant at first that the July 1 edition of the Kerrville Mountain Sun did not mention it. But, it did not stop raining.

Associated Press was the first to mention the impending catastrophe. Saturday, July 2, 1932, its affiliated Texas newspapers carried the news that “the Guadalupe river rose 30 feet within a few hours Friday, causing property damage of $50,000 to $100,000. The rise followed a 24-hour rain.”

That report further noted that a woman in nearby Legion had drowned, a “youth named Preior (sic) was clinging to a big tree in the middle of the flood a short distance from the Bluebonnet hotel here.” Ingram, Texas was under water. Telephone lines were down. No panic whatever in that AP news story issued sometime on July 1, which went to press all over the Lone Star State on July 2.

So common the flooding in Texas, so ho-hum the news, that the San Angelo Morning Times only excerpted a single paragraph from the AP item. The larger story: It was raining in San Angelo, a town that almost always is happy to see precipitation. Even the Houston Post, usually a reliable source of independent reporting, relied on the AP for its information.

News reports from affiliates of the United Press were also muted, with a different twist. Legion, Texas was important, because it was home to “an American legion tubercular camp near Kerrville.” Radio stations apparently focused on that tragedy, since military veterans were involved. UP reported only a 29’ rise in the Guadalupe, but also mentioned the youth who was marooned, omitting the part about a tree.

When the AP updated its reporting, those same newspapers dutifully carried the new information, often juxtaposed against the outdated data. Also on July 2, the Houston Chronicle informed its readers that four people had drowned, homes in the “river bottoms” had been swept away, Uvalde (in addition to Kerrville) was also scene of major flooding, and bridges had been washed out. And… the river was running far too fast to attempt search and rescue. Side by side with the earlier report of one dead.

The Bryan-College Station Eagle used the earlier AP report, adding that people in Harper, Texas had seen four people being swept down the Guadalupe near their town. Austin American-Statesman published both the AP and UP reports, adding a prominent text box stating that all campers hailing from Austin were safe. They incorrectly related that all four deaths were from a camp in the river bottoms of Kerrville. Fort Worth Star-Telegram also used both AP and UP reporting, adding a one-liner, apparently from their own research. “J. B. Early, maintenance engineer of the State Highway Department, said he believed state roads had been materially damaged.”

Despite its nonchalant report on page 1, the Austin American-Stateman added a worrisome postscript on page 2. Turns out, they really did not know if all those Austin campers in Kerrville were safe. They admitted that they simply had not heard whether flood waters had affected the camps.

The reporter then proceeded to name every camper from Austin and which camp they were attending. Seven boys at Camp Stewart. Four girls at Camp Mystic. Nine boys plus one mother at Camp Holland. Three girls at Camp Kiva. One girl at “the Presbyterian encampment.” Three girls at Camp Waldemar. With obvious relief, the reporter wrote, “A large party of girls has just returned from Camp Adelante.”

Miss Anna Hiss, advisory director of Camp Waldemar, had not taken her usual trip to that camp, so was available for an interview. She advised the reporter that no one at Camp Waldemar was in danger, because that camp had ensured that all its buildings — sleeping quarters and the three larger buildings — had all been constructed on a high hill. That would have been massive (and real) relief to the parents of the three girls at Camp Waldemar.

There would be little good news following those initial reports.

July 3, the Associated Press wires advised affiliates that the young man who had spent all night clinging to the branches of a tree had finally been rescued by Cooper Fletcher. The young man was identified as Hal Prior (sic), 18 years old (sic). However, rescue attempts had resulted in the drowning deaths of 40-year-old (sic) Charles Greenleaf and an unidentified youth from Camp Eagle.

AP also reported that Gov. Sterling had ordered men to Legion, Texas to rescue and house disabled World War I veterans stranded by flood waters.

Ham radio operators filled reporting gaps for reporters in places unaffected by the flooding. On July 3, Clarence Lawson (W5BSE) let the outside world know that while Camp Mystic and Camp Stewart had been washed away, everyone from those places had escaped to safety. Similarly, Eugene Butt (W5BSF) worked together with locals to get news to families and friends outside the flood area. Both Lawson and Butt answered questions from journalists as well, especially radio station KPRC in Houston.

Meanwhile, the Pedernales, Frio, Leona, and Nueces Rivers overflowed their banks. Perhaps not to the same extent as the Guadalupe, which had risen 50’ at Comfort, Texas. The waters had risen so high, had so filled the rivers and the creeks feeding into those rivers, that water had nowhere to go but up. Streets and alleyways became rivers. No one was safe.

A high-water bridge under construction was destroyed, and all the materials lost. A $30,000 high-water bridge in Center Point had collapsed. Mr. Early of the Texas Highway Department stationed men along all roads and highways leading into the affected areas, warning people to turn around. Mr. O.R. Seagraves, identified as a “Texas oil man,” refused the warning and drowned in flood waters “some distance from Kerrville.”

San Angelo Standard-Times noted San Angelo had only received an inch of rain. They were keeping an eye on San Saba, Texas. San Saba lies in the Llano River Basin. They had already seen a 36’ wall of water roar through town and expected it to reach 50+ feet before day’s end.

Also on July 3, the Flood Relief Committee of Legion, Texas passed a resolution and sent it to the County Commissioners of Kerr County. “… WHEREAS, in the opinion of the Legion, Texas, Flood Relief Committee, these losses would not have occurred, had these homes been located in an area beyond flood possibilities. THEREFORE, Be it resolved, that the Legion, Texas, Flood Relief Committee earnestly request the County Commissioners of Kerr County, Texas, to enact the necessary laws, or make some provision to prohibit the occupation or erection of any building as a home or for any other purpose in the area that in the opinion of the County Commissioners of Kerr County, Texas, may, in the future, be affected by floods of the rivers in Kerr County, Texas.”

Even as Kerrville, Uvalde, Comfort, Ingram, Legion, and other towns throughout the Hill Country struggled with all that water, Uvalde tried hard to celebrate the success of its native son, Speaker John N. Garner. Franklin D. Roosevelt had just nominated Garner to fill the VP slot on his presidential ticket.

Reporters made their way to flooded Uvalde to interview Garner’s son, Tully Garner, president of a local bank. The reporter interviewing Tully seemed disappointed that he could not gin up any excitement from the Speaker’s son. Really?

Instead of understanding the impact of the July 1932 flood, the nameless reporter concluded that Uvalde was choosing to wait until Speaker Garner returned home in September to plant his garden, a tradition the Speaker had long maintained. “No one meddles with the garden until Garner comes home and plants his own vegetables.”

Indeed, over the course of the next few weeks, even newspapers in Texas focused more on Garner’s nomination than they did on the aftermath of this flood. And the aftermath of the flood kept on coming.

On July 6, the Houston Post ran a lengthy list of highways that were still closed with no hope of reopening any time soon. Their staff had a tin ear, as next to that list, they published “Hambone’s Meditations,” by J.P. Alley, which had “Hambone” saying, “Folks gwine be in a bad fix ef’n it don’ rain ‘fo long — dry weather done jes’ about ruint dat golf link, now!!” [Thankfully, that thoroughly racist comic strip would be discontinued in 1968.]

Later that day, meteorologists and journalists warned people downstream what was coming their way. Before the US government built dams for flood control along Texas rivers, once a flash flood hit upstream, it would keep going, all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. That 50’ wall of water? It was headed to Victoria.

The Kerrville Mountain Sun resumed publication on July 7. And the stories they told were more horrific than journalists at the AP, UP, and Texas newspapers could ever have imagined. They gave names, they gave back stories, for those who died.

Comfort, Texas, downstream from Kerrville, indeed fared worse than Kerrville. Two couples in an automobile suddenly and without warning faced that 50’ wall of water. Miss Stieler (assistant postmaster in Comfort) and Mr. Bronson drowned. Miss Inguenhuett and Mr. Perkins managed to lodge themselves in trees. Which was only relatively better than the flood waters beneath them, as the trees were infested with snakes, also seeking higher ground. “It was only by constant switching with limbs from the trees that the reptiles were kept away from the marooned pair.”

The Mountain Sun also put name to the young man who died while trying to rescue Howell Priour. He was Mike Odell. One of the Mountain Sun’s reporters also spoke at length with Priour (and their report finally settled the confusion over that young man’s name). Priour provided critical testimony regarding the behavior of the Guadalupe River. Stuck in a tree for over twenty hours, he observed the rise and fall — and second rise! — of the river. The first crest happened during the day on July 1, he said. Around midnight, he saw a perpendicular offshoot of the tree he was stuck in become completely submerged. Priour’s testimony validates reports of that 50’ wall following the 36’ surge.

Priour’s story has all the makings of a made-for-Hallmark movie. He was seventeen, and curious. So he took his two collies down to the river to watch it rise. One dog ran into the water, the other followed. Priour tried to rescue his dogs, slipped while doing so. The dogs were washed downstream and died. Priour clung for dear life to a small cypress tree. As it submerged, he managed to move to a second, then after he nearly drowned, the river shot him into a much taller cypress.

The people at Cascade Swimming Pool across the river from Priour’s tree saw him. They aimed their giant spotlight directly at him. He told the reporter that that light made him less fearful. He was heartbroken when he learned that two people had drowned trying to rescue him. Six other would-be rescuers failed and had to be rescued themselves. One of those was a Mexican-American named Ben Calderon. Calderon was first to jump into the river in an attempt to save Priour.

Reports of heroism in Legion also filtered out. Twenty homes had been lost, and the veterans hospital was imperiled. The wife of a veteran hospitalized there led twenty children to safety on higher ground, while carrying her own 14-month-old child. A 50-year-old woman was swept into the river. Like Howell Priour, she managed to find safety in a tall tree. Three brave men rescued her by canoe. Bruce Storey, Herbert Kaiser, Jack Weaver. Mrs. Neal owed them her life.

Howell Priour’s rescue was about the only good news on the pages of the Kerrville Mountain Sun those days. The four dead (with corrected information) were: Mike Odell, 26, employee of Camp Eagle, hometown Houston; Charles Greenleaf, 50, hometown Olivet, Michigan; Ida Stieler, 29, Comfort; and, William Brunson, 30, of Austin.

Forty houses in Kerrville were swept away. Hunt, Texas was all but wiped out. Ingram was under water for hours. On July 7, the Mountain Sun posted an aerial photo taken on the 3rd. High flood waters stretched for miles on either side of the Guadalupe. The Meadows’ home some distance from the river was flooded up to the base of its windows. Mr. Meadows was still in shock.

Although all camps but Camp Waldemar suffered extensive damage, the Mountain Sun could report that there had been no deaths. Camp Stewart had lost half its cottages and announced it had started planning phases for rebuilding. Camp Rio Vista had lost around six cottages and like Camp Stewart, was in the planning phase to replace them. Arrowhead Ranch (a boy’s camp), Camp La Junta, and the San Antonio YMCA Camp had only lost diving boards.

Camp Mystic said (!) it would be rebuilding its lost cottages on higher ground.

Sanitary engineers arrived on scene on the 7th, testing drinking water across the region, armed with typhoid serum just in case. Headlines proclaimed there was no reason to worry about contracting typhoid fever. In smaller print, buried in the back pages, names of locations where well water was indeed contaminated, where typhoid shots were administered. Hundreds received those life-saving shots, while contaminated wells were treated with chlorine.

As grim as things were (and they were very grim indeed), residents of Kerrville managed to find humor in the flood’s aftermath. A man who had been camping along Quinlan Creek (also flooded) returned to his cabin to find a new table in his room. It had floated in from somewhere. On that table was an intact package labeled, Keep in a cool, dry place. A woman returned to her residence to find that not only had her nightstand floated to the top of the flood waters, but her alarm clock still stood bravely on its surface. Still ticking.

Several amber and orange cottages from Kerrville Cottage Camp had been uprooted and dumped by flood waters in the middle of the green and white cottages of Bass Courts. A huge cypress tree from a tourist camp eleven miles away was deposited at Glen Rest Cemetery with its “Manager, Ring Bell” sign still affixed. Further, Quinlan Creek floodwaters had left the 11’ cypress on top of other, similar cypresses, making it look seventy-five feet tall. Dark humor, but still.

By July 14, journalists and rescuers had been able to take stock of the flooding event. The Mountain Sun confirmed that deaths were minimal, because the flood warning system along the river had functioned properly. After the initial wall of water, and subsequently as the river rose at the rate of 3’ per minute, campers had been able to seek high ground. “It broke all previous records for height,” they said.

“Had the flood came (sic) down at night, the loss of life might have been appalling, according to old-time residents who know the Guadalupe,” so wrote the Mountain Sun.

The Mountain Sun’s good reporting perturbed Kerrville’s city fathers. All this talk of typhoid and destruction was driving tourists away. City and county health officials made public statements, reported by the Mountain Sun, stating that there was no outbreak of typhoid, that all camps including Mystic had reopened, and that the Guadalupe River was safe to swim in. (Page 1)

On page 12, those same officials admitted that wells had been contaminated, but they had been taken care of. And yes, people had received the typhoid shots, but only as a precaution. “Post-flood sanitation and health measures have been declared a huge success.”

Thursday, July 14, Camp Mystic bolstered that PR campaign by issuing Volume 1, No. 3 of Mystic Murmurings, edited by Miss Margie Bright of Fort Worth. “The paper indicates strongly that the Mystic spirit was unabated by the flood and its immediately following inconveniences.”

Just in case, that typhoid program continued throughout the summer, with a total of 1,150 people receiving the shots. Kerr County also promoted smallpox and diphtheria vaccinations for school-age children.

County Commissioners wrapped up the summer of 1932 by voting to lengthen an existing low-water bridge. It was to span a new channel made by the river during the July 1 flood.

They had finally put the flood of July 1932 behind them. Tourists once again came to Kerrville. Campers said teary goodbyes before heading back to Houston, San Antonio, Austin for school. Fishing industry was doing great. All was right with the world.

No one could have known. This could not have been predicted. There will never be a flood like this one. Heaviest rains in the history of Texas.

Part 3: “There is really, absolutely positively, no way we could have seen this coming” — Floods from October 1932 through 1987.

References. No bylines in these early news articles.

Austin American: September 11, 1921, p. 1; September 13, 1921, p. 1; July 2, 1932, p. 1; July 6, 1932, p. 1.

Austin American-Statesman; July 2, 1932, pp. 1, 2.

Bryan-College Station Eagle: July 2, 1932, p. 1.

El Paso Herald-Post: July 2, 1932, p. 1.

El Paso Times: July 3, 1932, p. 1.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram: July 2, 1932, p. 1.

Houston Chronicle: July 2, 1932, p. 1; July 3, 1932, p. 2.

Houston Post: September 11, 1921, pp. 1, 2; September 12, 1921, pp. 1, 5, 9; September 13, 1921, p. 1; Editorial, September 14, 1921, p. 6; July 2, 1932, pp. 1, 7; July 3, 1932, p. 1; July 6, 1932, p. 2.

Kerrville Mountain Sun: March 20, 1930, p. 12; May 15, 1930, p. 1; October 9, 1930, p. 1; October 23, 1930, p. 3; March 26, 1931, p. 5; June 23, 1932, p. 9; July 7, 1932, pp. 1, 5, 8, 10; July 14, 1932, pp. 5, 6, 9, 12; July 21, 1932, pp. 1, 12; July 28, 1932, p. 5; August 4, 1932, p. 1; August 11, 1932, p. 1.

Kerrville Times: November 26, 1931, p. 1.

Kilgore News Herald: July 3, 1932, p. 1.

San Angelo Morning Times: July 2, 1932, p. 1.

San Angelo Standard-Times: July 3, 1932, p. 1.

Sunday’s post will cover the second flood of 1932 in Kerrville, as well as the floods of 1936, 1952, 1964, 1972, and 1987. As you read, keep in mind that as devastating as all these floods were, they represent only a small number of the many, many deadly floods that have hit Texas through the years.

© 2025 Denise Elaine Heap. Please message me for permission to quote.

Now More Than Ever is a reader-supported publication. To receive email notifications regarding new posts, and to amplify my voice here on Substack, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

If you’d simply like to leave a tip for this specific post, I would be grateful!