Texas as seen through the eye of its hurricanes. 1900-1912.

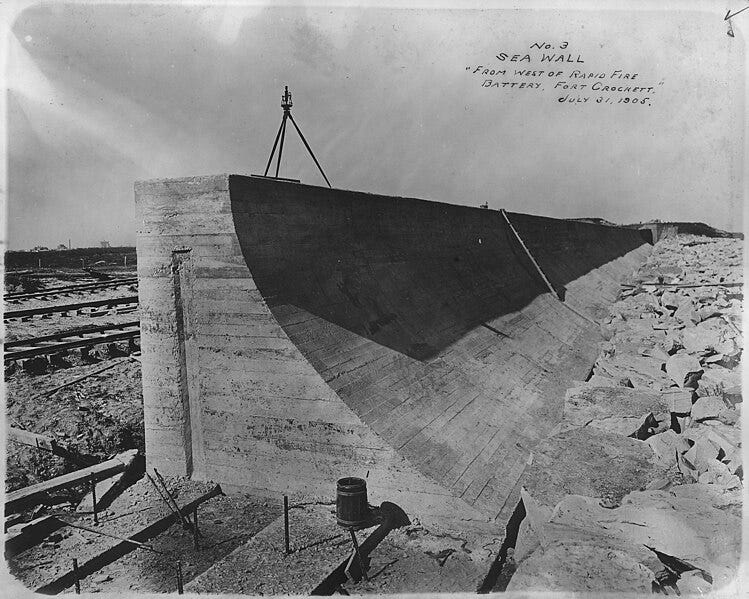

The seawall formed the city’s first line of defense. Raised elevation of the island was its second. And the causeway served as indestructible link to the mainland. Galveston was impregnable!

Part One: August 19, 1886 - September 8, 1900 (first two days)

Part Two: September 10, 1900 - September 23, 1900

Texas’ response to the April 1906 San Francisco earthquake

On April 18, 1906, as Houston businessmen headed to the office, newsmen across the United States rushed to report bulletins that came in over the wires from the West Coast. An earthquake of unbelievable magnitude hit San Francisco at 5:13 a.m. Papers said that the earthquake had rocked not only San Francisco, but also suburbs down to Palo Alto. Death and destruction continued nonstop.

“Water and sewerage are spouting into the streets from broken pipes,” Texas’ Palestine Daily Herald reported. “The thoroughfares are obstructed with debris, and the street car tracks are twisted out of shape. Gas from the busted mains is escaping on the streets. The fires continue to spread in all directions. The destruction of the entire city is now feared.”

Early counts of the dead ranged from 300 (actual bodies retrieved) to 20,000 (estimate from Vice President Fay of the Southern Pacific railroad). Wire service had been disrupted as soon as the first quake hit, so any news past 5:30 a.m. Pacific Time came mostly from wild speculation. Reporters from Los Angeles traveled as quickly as they could to San Francisco, but it would be another day before they could see the devastation for themselves.

As had been the base with Galveston’s devastating hurricane, American citizens wasted no time coming to the aid of their own. On April 19, 1906, the U.S. Senate approved $500,000 [$15 million] in federal assistance for “San Francisco earthquake sufferers,” but when the measure reached the House, it was increased to $1 million [$30 million].

Kansas City, Missouri and Lincoln, Nebraska were the first two towns to offer help to The City By the Bay: “Whatever you need,” they said on April 19. That same day, J. Piermont Morgan wired $25,000 of personal funds to the city’s relief fund.

By the April 21, almost all of the United States had pitched in. Boston sent $100,000, a down-payment on its pledge of $3 million. Los Angeles dug deep and contributed $100,000. Chicago raised $373,645, with a goal of $1 million. Philadelphia forwarded $500,000 immediately, with more on the way. Pittsburgh sent $225,000 from city coffers, and Andrew Carnegie promised that his steel companies and ‘hero fund’ would each donate substantial amounts. Multiply by 30 to understand the outpouring of relief funds.

New Jersey’s legislature wished to subscribe $1 million to San Francisco’s aid. Their state’s surplus was only $3 million, and it was doubtful that they could scrape together the votes to approve giving 1/3 of the surplus away. But the mayor of Paterson, New Jersey reminded his fellow citizens that when their town had been devastated by a great fire four years earlier, San Francisco had been the first city to help them.

Small towns across upstate New York rallied behind San Francisco. Schenectady cancelled its Fourth of July carnival and sent the entire $6,000 budget for that affair to the West Coast. Elmira, Watertown, Utica, Troy, Rome, these communities plus Duluth and Superior, Minnesota sent $25,000. Each. Cincinnati, New Orleans, Atlanta, Baltimore, New York City, Cleveland, and Detroit – each collected large sums of money and supplies for neighbors whose lives had been ruined in an instant.

The American Red Cross saw its coffers swell by $38,055 in forty-eight hours, all earmarked for San Francisco. The Masons urged lodges across the nation to take up collections. Labor unions passed the hat. Even professional baseball’s National League sent $1,000.

Texas lagged well behind the rest of the nation in giving to fellow citizens who found themselves without a roof over their heads, without potable water, without food or basic supplies. One would think that after “Galveston” in 1900, Texans – especially Houstonians – would have been first in line to wire funds to San Francisco, and that donations would have exceeded the rest of the nation in scope and generosity.

As it stood, Houston and Galveston could only come up with $10,000 each, despite the financial windfall the Gulf Coast had seen with the Spindletop gusher in 1901. Estimates by April 22 showed pledges of $100,000 for the entire state. Indeed, that amount would not be exceeded after all gifts were tallied. Farms in California, not Texas, boxed up food and shipped it to San Francisco.

Many Texas towns did not bother setting up their own relief funds. On April 20, Palestine noted that it supposed it should do so. “Let us respond to the distress call of our friends,” the Daily Herald said. But instead of setting a goal and raising money, they left it up to townsfolk to give money individually, money the newspaper then would forward to the West Coast.

The same paper followed up the next day with the exhortation, “If you feel an inclination to be charitable, the sufferings of the victims of earthquake and fire at San Francisco give you full opportunity to exercise that inclination to its limit.” Again, no call for a city-wide target, just a general summons to give.

Brownsville followed the same pattern. On April 23, its Daily Herald noted, “The Wells Fargo Express Company has announced that it will transmit all money and goods intended for the relief of San Francisco earthquake sufferers, when addressed to relief committees.”

Both Palestine and Brownsville would eventually hold a “benefit for Frisco sufferers” on April 26, but events in both towns doubled as a marketing ploy for their skating rinks. At least reporters in Palestine noted this: “It was very generous in (sic) the management of the rink to devote the proceeds of their business for the night to this fund, and will add to their already increasing popularity.”

Even as Texas citizens, businessmen, and newspapers lagged well behind the rest of the nation, William Randolph Hearst matched J. P. Morgan’s generosity. Hearst wired $25,000 from his personal account to purchase food and supplies.

A family in Texas received a letter from friends in Stockton, California, a letter which would be published in Texas newspapers. The correspondent described a California businessman named J. D. Phelan who had seen several million dollars worth of his real estate holdings destroyed by fire in San Franscico. Yet Phelan opened his pocketbook and donated $1 million to the relief effort.

So great was the outpouring of aid from people across the United States that President Roosevelt refused all offers of assistance from foreign powers. The German government was especially disappointed and published an open letter to the president: “Will you allow us to correct this false impression so that our friends in Germany may be permitted to follow the dictates of their heart and contribute?”

Acting Secretary of State Robert Bacon assured Germans (and indeed, people across the face of the globe) that “the president wishes the German people to understand how deeply we appreciate their hearty sympathy,” but that the people of the United States of America had amply met all the needs of San Franciscans.

By April 30, San Francisco was even able to tell the War Department that it could hold off on sending all 2,500 troops that had been promised. It would be enough if they could send only 1,350 men, and save the $100,000 that would have been spent on transporting the remaining 1,150. They needed rations and water more than they needed manpower.

Events in San Francisco would have made Texans feel vindicated in their white-supremacy attitudes. There were reports that law enforcement in San Francisco shot “ghouls” (Japanese) on sight. “The Japanese are making themselves a terror to defenseless people in some districts,” Texas newspapers said. From what Texans read, only the Japanese and Chinese looted. ‘Good whites’ endured misery on their account, the papers said.

On April 27, the Palestine Daily Herald noted, “Most every disaster has some attending good. San Francisco has gotten rid of her notorious Chinatown, and it is a safe prediction that it will not be rebuilt again in as prominent [a] location, if at all.”

September 1906

1906 was another bad year for hurricanes too, but Galveston (and Houston) suffered no direct hits. The September 27 hurricane (later called the “1906 Mississippi hurricane”) caused substantial damage from New Orleans to Pensacola. That storm wiped out Mississippi’s cotton crop, already harvested and baled. Although there were far fewer deaths, loss of property greatly exceeded the 1900 Galveston storm, $12,000,000 [$360 million] attributable to ruined cotton bales alone.

In 1906, Pensacola endured a second hurricane. The hurricane wreaked havoc in Nicaragua and Cuba, but because it doubled back on Florida (moving through the state twice), losses were greatest there.

Once again, Texans proved extraordinarily stingy. There were no calls for “relief” or proffered assistance to neighbors in New Orleans, Mississippi, and Pensacola. Instead, the Houston Post gleefully noted that, “If cotton advances another cent a pound, soon every girl in Texas will be married by Christmas.”

August 27, 1909 – Corpus Christi

Politicos and society mavens alike were all atwitter in early August 1909 when President Taft announced his travel plans for September and October 1909. He would visit his half-brother Charles Taft in Corpus Christi, Texas. Following that visit, the president would stop at Houston before proceeding to New Orleans. Preparations began at once in Houston and Corpus Christi. Everything had to be perfect!

Two weeks later, residents of Galveston (and Houston) held their collective breath. A Category 3 hurricane barreled down on the island. Although it technically came ashore at Freeport, this was the closest to a direct hit that Galveston had sustained since the storm of 1900.

Hurricane Four brought a ten-foot storm surge to the Texas coast. And the new seawall held! All property damage and deaths associated with the hurricane took place beyond the wall.

In total, forty-one people were killed, with $2 million [$60 million] in property damage. Hardest hit: Tarpon Fishing Pier, a new resort on the north jetty, six miles from the city across the bay. It had twenty-five furnished rooms, was two stories high – and had just opened earlier that same year.

Deaths included Mr. Peatshorn (the son of a book dealer), and Mr. C.H. Daily (Circulating Manager of the Galveston Tribune). After listing the names of those who had died in the storm, the reporter added, “and four negroes.”

As soon as the winds and storm surge retreated, Galveston was back to business as usual. The single railroad bridge linking the island to the mainland was damaged, necessitating use of tugboats, ferries, and barges as primary means of transportation should one desire to travel to Houston. But city fathers were pleased as punch with themselves. The substantial investment made in building the seawall and raising the island above sea level paid for itself many times over.

May 1910 – Gulf Coast, Houston and Beaumont, not an official hurricane

In May 1910, nature dealt Houston a blow. Two nights back to back, tornadoes and fierce storms roared across South Texas. Houstonians may have been used to summer’s severe thunderstorms, but these? These storms were of an intensity rarely witnessed along the Gulf Coast.

The El Paso Herald would describe them as “windstorms of cyclonic proportions.” The first night (Thursday, May 19), the damage primarily affected oilfields near Houston. Fifteen derricks were destroyed. Otherwise, the high winds and occasional tornadoes flattened farmland.

But that included the residence and outbuildings of the T.C. Smith family, seven miles north of Houston (now well within Houston’s city limits). And the storm also struck the home of J.L. Mouse, killing his 11-year-old boy and injuring his other three sons.

As the storm continued to rage, more people were affected. Friday night, twenty towns reported houses “blown away or damaged.” Beto Hernandez was killed by a lightning strike.

All told, at least a dozen people were injured. Those like my great-grandfather who had electric or telephone service experienced significant disruption, as the storm took out utility poles. For this not to have been an official hurricane, the storm’s destructive might astonished Houstonians.

It would not stop at the coast, however. The storm tracked westward, eventually wreaking havoc on Dalhart, Texas (a lightning strike took out the telephone plant, stunning the only person on duty). It barely let up as it kept moving westward, through El Paso and into New Mexico. The high winds and lightning did not seem to diminish as it inched across the state, not petering out until the end of the first week in June.

Long-term results of the 1900 Galveston hurricane

As could be seen in 1912 platform of the Texas Democratic Party, coastal infrastructure had grown in importance for residents of the Bayou City (Houston). The interstate canal would in fact become a reality, though it would be called the Intracoastal Waterway (in Texas, the Intracoastal Canal).

The week of the Democratic State Convention, residents in Galveston and Houston celebrated the opening of the Galveston Causeway. A modern bridge replaced the flimsy wooden piers that had been destroyed by the Hurricane of 1900. Texas had copied the architecture employed in the Florida Keys by the Flagier railroad.

The causeway had been constructed of mixed materials: Stone arches rested on “a foundation of thirty piers sunk to a considerable depth below the bay’s bottom.” The piers were made of concrete and steel, and the 100-foot drawbridge was all steel. The sides of the bridge were also fabricated of concrete and steel, as was the “curb” along the roadway. City fathers had demanded strict inspections to ensure the construction was sound, that no shortcuts had been taken.

Galveston envisioned the causeway as the third element of its post-1900 protection of the island. The seawall formed the city’s first line of defense. The raised elevation of the island was its second. And the causeway would serve as indestructible link to the mainland. Galveston boasted that these three things taken together “will make Galveston impregnable.”

Now they just needed to upgrade the awful caliche roads that connected Houston with the island! And pretend that the dratted new port of Houston wouldn’t be opening soon.

Excerpted from One Family’s Houston, © 2012, 2024 Denise Elaine Heap. Please message me for permission to quote. And of course, please feel free to share!

My sources: Diary of my great-grandfather. Grandmother’s memories. Accounts of the Galveston hurricane, San Francisco earthquake and other hurricanes and natural disaster as related by the Houston Post, New York Times, and other major news outlets. (Thanks to newspapers.com for such a valuable resource — started in Texas by University of North Texas in the early 2000s, carried on by Ancestry.)

I was born and raised in Houston, on the same farmland — then inner city — my great-grandfather purchased in 1908. In Texas schools, we learned that Texans are the most generous people on the face of the earth.

As you can see from “real” history, if the rest of the United States of America had to depend on Texas towns and cities instead of FEMA following natural disasters, that would not be a good thing. Even as Texas was awash in oil money after 1901, Texans failed to respond generously to the plight of San Franciscans, despite San Francisco’s outpouring of much-needed help in 1900.

Social safety nets are only as good as their design.

Now More Than Ever is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber as a statement that you stand with me and with all those who understand what ‘privatization’ of NOAA and National Weather Service, not to mention FEMA, would do to our country!