Give yourself grace

Give yourself grace. It’s not worth the effort of beating yourself up, of trying to figure out what’s wrong with you. Nothing is wrong with you. You’re human. Embrace your humanity.

Trigger warning: Suicide.

It had been like most Tuesdays, that December 13, 1977. I’d gotten in late the night before, Schnellzug from Munich. I’d slept in, then gone to class, finally getting used to German university classes, where very few students show up. Except for the final.

Maintaining that American-ness, something as simple as going to class, had given me access to two brilliant minds, Augsburg professors who liked my non-traditional topic—Political Humor as Informed Dissent—and egged me on. Dr. Weber had included me in his family’s Thanksgiving dinner only a few weeks prior. The blessing of familiarity.

We were the first Fulbrighters in Augsburg. First students to live in brand new dormitories on Franzensbadstraβe. And among the earliest students to attend the university after it was accredited in 1970 as a full-fledged Universität, instead of a ‘mere’ Technische Hochschule.

Life in Augsburg was young and old, fresh and fusty. In 1977, the Rathaus still bore signs of the war. Inside, prewar splendor had been replaced with gray, drab drywall. The city had rebuilt, yes, but minimally, just enough to regain a semblance of normalcy. Augsburg-Göggingen, home to the newish university, sported more concrete than grass, more bauhaus architecture (read, prefab) than Gothic or baroque.

These factors had created a beautiful perfect storm of community. Because of its newness and lack of rentable rooms, Augsburg students tended to live in the dormitory, unusual for Germany, especially in 1977. The university had been slow to install infrastructure, so we had only one telephone per floor. 1977, so of course no Internet, much less WiFi. Those were distant dreams.

Lack of infrastructure drew us together. Although I am not Catholic, the Katholische Hochschulgemeinde (KHG) or Catholic University Parish adopted me. As did my next-door neighbor, a young woman from Bamberg who taught me all sorts of delicious German trivia. My room was next to the entrance, and since every room had an outside door leading to a small patio, quite often friends would come through my room, just to chat.

It was such a nice setup. I’ve probably never lived in a place where community was so strong, neither before nor since.

I therefore thought nothing of it when someone knocked on my door. “Hey, there’s a phone call for you. Some guy from Munich.” Hmm, what had I forgotten as I left the night before? Although it seemed odd for them to call, I remained unsuspecting.

The cryptic conversation shed no light whatever on the mystery. The voice merely told me to go to the post office to pick up a telegram. Wha-at?

I remember it was a freezing cold day. The route to the post office (and shopping district!) was well-worn. I’d walked it a million times, as usual taking the back streets, avoiding traffic on Friedrich-Ebert-Straβe. It was odd that laundry was still on the clothesline behind one farmhouse, frozen stiff. Normally I could set my internal daily clock by that home’s activities. And Monday was laundry day!

Once the postal employee handed over the telegram, everything went black. The next few days, if not weeks, became a horrid blur. I could not stop crying, not for anyone, not for anything.

Because my little sister Janet had suicided the day before.

It would be weeks before I knew more, before letters from home arrived. It would be months before I could go out in public without utterly falling apart. It would be years before December 12 was halfway normal. It would be “never” before the occasional gut punches went away.

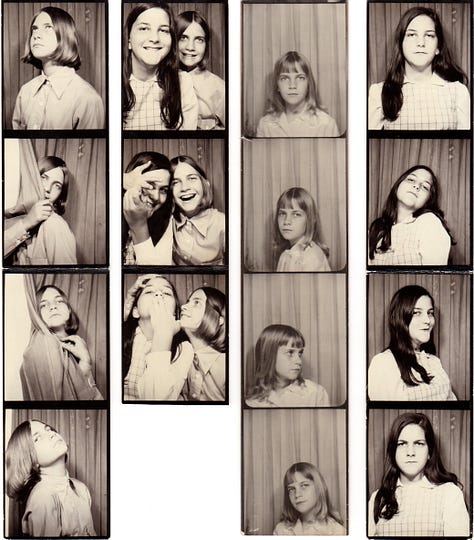

When I left for Germany in October 1977, it seemed as if Janet’s life was back on track. After ten years of drug and alcohol addiction, after years of believing the lies of one man after another—men who wanted a notch on their bedpost, who wanted her beauty, not her—after having a son by one of those serial snakes… After all that, in October 1977 it looked like she was finally clean and sober for good. Like she had finally understood her value, her immense genius. Like she had finally grasped that she was far more than a pretty face.

A year earlier, she had completed her GED. A year earlier, she had detoxed and avoided temptation. A year earlier, she and my mom had a hard conversation about what it would take for my parents to hand her son back to her. Tough love, and it seemed to be paying off.

On December 11, 1977, my mother and Janet spent a full day together, chatting about Janet’s job (loved it!), about her boyfriend (love of her life!), about her apartment (sooo darling!), about Jason (handover soon!), about life (never better!).

Indeed, the letters I received after December 13, written in the weeks before, echoed all that optimism.

And then on December 12, 1977, with the love of her life walking out on her, and convinced that her boss hated her guts, she stole my father’s pistol, went back to that darling apartment, and shot herself in the heart. Her best friend found her lifeless body.

Although what followed is a blur, there are highlights that have stuck in my memory all these years later. Dr. Ernst Krzywon knocking on my dorm door, sitting with me as I wept. Dr. Albrecht Weber and a couple of other professors bidding me rest in their offices as I tried to go to class, struggling to keep putting one foot in front of another.

My KHG and dormitory friends created a safe space, a safety net, around me. If I needed to talk, they listened. If I needed to be quiet, they read textbooks or wrote papers in my room, letting me Be, while ensuring I was all right. Do you know how much that means?

Friends in Munich sent notes, letters, cards, invitations to stay with them. When I took them up on those invitations, they didn’t press me, just let me cry.

The Fulbright/DAAD people granted me space as well. When my parents asked if I could spend time with them instead of going to Berlin over spring break, the German Fulbright office didn’t hesitate with their “of course.” I had three weeks in Germany with my mom and dad, most of the time silent, just being together.

My parents told me of the outpouring of love they had known since December. Family who showed up for the funeral. Food dropped off. One of my high school friends (hi, John) grieved with them, quietly, maybe saying two words the whole time. They never forgot him. Of all my friends, he was their favorite, for ever and ever, Amein.

For years and years and years and years and years, I bawled my eyes out on December 12. And on February 26, Janet’s birthday. The death of parents or siblings or spouse or children is hard enough. There’s something about the suicide of a parent or sibling or spouse or child that cuts deep. It’s a wound that never heals.

Around 2000, I could finally face the week of December 12 without totally falling apart. Yes, it took that long.

But there’s still a pall that falls over December in the lead-up to that date, and in the days following. It’s a strange cycle, something on my insides that knows something’s wrong, even though the sorrow is no longer as palpable. It’s still there. More quietly there, but there.

The first few years of this quieter grief, I would beat myself up for not being over it, for still feeling that decades old pain. Surely there’s something wrong with me, something I should do differently. If only I were stronger, if only I could get a better handle on my emotions.

You know what? That is stuff and nonsense. That cycle of grief, the dark cloud that starts descending come the second week of December, that means I’m human. It means I haven’t stopped feeling. It means my “gut” is still functioning, that I am still alive.

I have learned, and am continuing to learn, to grant myself grace.

It’s much easier for me to empathize with the pain of others. I’d wager you are the same way. You know what to do, how to express sympathy, if friends or family experience one of life’s devastating events. You know when to bake, when to shop, when to buy flowers. You’ve likely mastered the art of listening, of being silent, of being present.

You know how to grant others grace.

When it comes to yourself—when it came to myself—it is much, much harder. There’s a false doctrine that teaches we must be strong. There are fake life coaches who tell us to buck up, to go to therapy (not knocking therapy!), to adopt a stiff upper lip. Everywhere you look, there’s someone who has the surefire solution for internalizing that grief.

Nope. Ignore them. Give yourself grace. It’s not worth the effort of beating yourself up, of trying to figure out what’s wrong with you.

Nothing is wrong with you. You’re human. Embrace your humanity.

Give yourself grace.

Postscript #1: December 1977 was a hellacious month for the Heap family. December 3, my Uncle Jimmy died in a freak drowning accident in Taylor, Texas. He had just recorded his final album and retired from the Country-Western music scene. He wanted to enjoy life with his family after years on the road.

He had always gone home to Taylor—Houston, Nacogdoches, Memphis, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, those had been stops on his rise to fame. He had finally had enough. Now he could enjoy Jerry Jo, Joey, and David. They mattered.

My parents and Jerry Jo traded funerals, traded memories, traded sorrow.

A hellacious December indeed.

Postscript #2: About two months after Janet’s suicide, my parents were driving home down I-10, headed west under the West Loop spaghetti bowl. My dad spotted something on the side of the road and pulled over.

A young woman about my sister’s age had jumped from the top level of Houston’s West Loop. Her suicide note said she was upset about a bad haircut (and of course that would not have been the reason).

My parents waited until her parents showed up, comforting them, holding them, grieving with them.

Our grief calls us to be there for others.

© 2025 Denise Elaine Heap. Please message me for permission to quote.

Now More Than Ever is a reader-supported publication. To receive email notifications regarding new posts, and to amplify my voice here on Substack, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

If you’d simply like to leave a tip for this specific post, I would be grateful!

I never met Janet, but I know she was lucky to have you in her all too short life. May she rest in eternal peace and GRACE. 🕊️

Gwen

Thank you for pouring yourself into these memories on behalf of your readers, Denise. Learning to give ourselves and others grace is the work of a lifetime. I'm so sorry for Janet and the many who loved her. And I'm glad that you received such kindness from others so far from home. 🤍